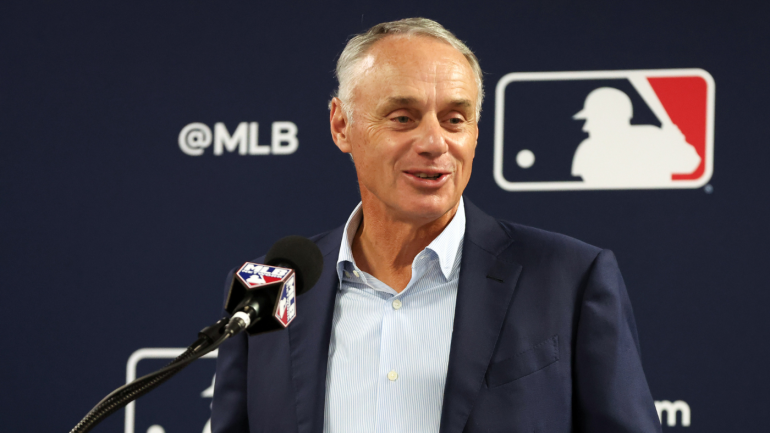

Earlier this year, Major League Baseball commissioner Rob Manfred announced that he will not seek reelection when his term ends in January 2029. Manfred, who first assumed the post back in 2015 by succeeding Bud Selig, may not have always said agreeable things or made popular decisions -- though the rule changes he helped institute last year seem like a point in his favor after a season of play -- but there's no denying he's led the league to great financial growth for the owners and has left his mark.

What's left on Manfred's to-do list? Only time will tell for sure. He's already signaled that he would like to set up MLB to expand to 32 teams by the time he walks away. "Those teams won't be playing by the time I'm done but I would like the process along and [cities] selected," Manfred told reporters in early February.

Manfred's desire to expand is nothing new. In the past, though, he had couched it by adding that he would only pursue that option once the Tampa Bay Rays' and Oakland Athletics' stadium situations were resolved. With both teams seemingly nearing solutions, it makes sense that Manfred would shift his thinking to adding new clubs.

Should Manfred's vision come to fruition, it would represent the first time MLB has expanded since 1998, when the Rays and Arizona Diamondbacks began play. As we here at CBS Sports chronicled back in 2019, MLB has now gone without expanding longer than at any point since first breaking the seal back in the early 1960s.

To wit, here's a brief timeline of MLB expansion since then:

- 1961: Los Angeles Angels and Washington Senators added

- 1962: Houston Colt .45s and New York Mets added

- 1969: Kansas City Royals, Seattle Pilots, Montreal Expos, and San Diego Padres added

- 1977: Toronto Blue Jays and Seattle Mariners added

- 1993: Florida Marlins and Colorado Rockies added

- 1998: Tampa Bay Devil Rays and Arizona Diamondbacks added

You may have some questions about this process, including why MLB wants to expand to 32 teams and which markets are most attractive. Slowly scroll with us down the page as we do our best to provide you with the answers.

1. Why would MLB want expansion?

Naturally it's to spread the wonderful sport of baseball to as many passionate fans and deserving markets as possible. Oh, who are we kidding here? It's because of the money.

John Helyar wrote in his 1994 book "The Lords of the Realm" that, to that point in time, "expansion was never the pursuit of new opportunities; it came always as a response to a problem." If that dynamic remains true, then the problem solved by adding two teams is that the other owners want more money. Expansion is a relatively painless way for the league to make more moolah through various means: by drawing more fans through more gates; by luring in new media deals, at the local level during the regular season and, eventually, nationally with further expansions to the postseason; and so on.

There are other benefits to expansion -- spreading the game; capturing new markets; creating new jobs across the industry; balancing the talent level; and so on. Many of them, though, boil down to making more money for the few who run the sport.

In fact, the very process of creating teams requires the new folks to pony up.

2. How much will the expansion fee cost?

We can't say for certain, but we can make a guess. The last time MLB expanded, ahead of the 1998 season, the Tampa Bay then-Devil Rays and Arizona Diamondbacks each had to pay $130 million to join the club. We feel confident the price has gone way up.

Consider that the National Hockey League's Seattle Kraken paid a $650 million expansion fee to join the league in 2021. Even that was a healthy boost over the $500 million the Vegas Golden Knights paid a few years prior. MLB is a far more lucrative league than the NHL, suggesting that its expansion fee should easily top $1 billion. Manfred himself floated a fee of more than $2 billion when asked in 2021.

But let's stick with a $1 billion expansion fee for simplicity. That would leave the original 30 club owners raking in nearly $67 million apiece just for granting the new kids entry to the club. You can understand, then, why those 30 owners are willing to make room at the table.

3. What makes a market enticing?

Back in 2019, we asked that very question of Pat Williams, a longtime NBA executive who attempted on several occasions to land an MLB team for Orlando, Florida. Here's what Williams told us:

When Williams is asked what he'd advise current groups jockeying for a team, he ticks off the same three categories everyone else identifies as vital. He first says to make sure the owner, or group leader, has deep pockets. He then talks about the importance of a stadium, or a plan for a stadium. At last, he addresses the community aspect, noting how selling season-ticket deposits door-to-door helped Orlando land the Magic in the first place. Williams then seems to add a fourth aspect to his list: himself -- or, a proxy who is enthusiastic and committed. In his own words, someone who is "going to so many chicken lunches" to woo the community "that at night he doesn't sleep, he roosts."

To recap: a very rich owner, a stadium (or workable plans for one), a rabid community, and an indefatigable salesperson who can pull it all together. These days, we would add a few more items to that checklist, like a city governance willing and able to offer public funding, and perhaps some land-development rights at and around the stadium site.

Speaking of which ....

4. Why are mixed-use ballpark sites so popular?

If you've been paying attention to stadium matters over the last decade or so, you've probably noticed that one of the recent trends is the popularization of the "mixed-use" stadium site. That is, in essence, when teams build districts around their ballpark, complete with places to eat, shop, and generally spend as much time and money as possible.

We previously talked to Josh Frank, an urban designer and town planner, about why teams found the mixed-use model so enticing:

Finding a pre-existing location with those attributes is as common as finding a Joshua tree in the rainforest. Teams have adapted to this reality by building districts of their own -- be it the Battery, or Texas Live!, a bar/restaurant/shopping complex built adjacent to the Texas Rangers' new ballpark opening next year. The "mixed-use" approach so often touted by owners is more beneficial to the teams in the long run, anyway. As Frank notes, teams can make greater profits by developing then selling the land. The stadium becomes a secondary motivation -- the bait for others, not the score. Alas, teams having control over what -- and who -- is next door creates further complications. "What these teams are trying to do is create their core demographic in a district," Frank said. "White male, medium to high income, tech-oriented."

It stands to reason that any city willing to offer additional land and revenue options to teams -- such as the ability to construct a Braves- or Rangers-like mini-town around the field -- would have a leg up on the cities unable to make that commitment.

5. Which markets make the most sense?

We will, in closing, defer to our Dayn Perry, who humbly offered the following cities as intriguing candidates: Nashville, Salt Lake City, Charlotte, Montreal, Portland, Las Vegas, San Antonio, Sacramento. You can read more of Perry's analysis here.